Defending MLaaS Systems

Submitted at the Qualification Round of the Embedded Security Challenge at CSAW 2022. This report helped us secure a spot in the finals, being one of the 12 finalists from all the regions worldwide. The report can be viewed in its original format here

Introduction

ML models have experienced great success in computer vision, natural language, and various other tasks. Following their success, several companies have launched or are planning to launch cloud-based ML as a service (MLaaS) models. Users have the option to submit data sets, have the service provider perform training algorithms on the data, and then make the model outputs broadly accessible for prediction queries. The entire backend interaction between the user and the model is taken care of using easy-to-use Web APIs. With the help of this service architecture, consumers make the most of their data without having to build their own ML infrastructure. But these algorithms and infrastructure aren’t designed with keeping security in mind. More often than not developers end up with vulnerable systems. In this report, we review defenses against popular attacks on MLaaS systems.

Threat Model

To understand and mitigate attacks on MLaaS, we first list the key elements that are in play when hosting machine learning systems on the cloud. MLaaS services usually have a query endpoint (API) to the trained model which runs on the backend, receives input from the user, and returns model predictions. We have three main players: model owners, model users, and adversaries.

The model owner is the entity that hosts the model on the cloud, they have access to model weights and architecture and control who can use their MLaaS. Model users have access to the query endpoint that the MLaaS exposes. Adversaries are malicious model users trying to exploit the system. If the adversary has no information about model architecture and data distribution, we can call it a black-box system, while if they have full or partial access to this information, it’s a grey box model. The threat model includes three assumptions about the adversary: goals, capabilities, and knowledge. As defenders, we are unaware of whether a particular user is benign or malicious.

Risks to MLaaS Systems

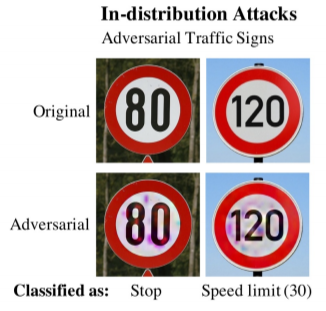

MLaaS systems face a variety of risks from adversaries. Consider the recent event where McAfee security researchers placed black electrical tape over part of a 35mph speed limit sign to extend the middle of the “3” slightly. The camera in the automobile misunderstood the sign as 85 mph due to this minor modification. The cruise control system then immediately accelerated towards this target. 1

-

Evasion Attacks: The above example is a typical case of a carefully crafted Evasion attack, where the adversary can get the model to misclassify an example by manipulating attack samples. The motivation behind these kinds of attacks can be anything from escaping a spam classifier to causing human damage.

-

Extraction Attacks: Evasion is not the only way to exploit/leak data from a model. We have model Extraction attacks where adversaries craft clever examples to extract the learned weights from a model and then reconstruct a student model that can match the teacher’s performance to a remarkable level. The main objective of these attacks is to save resources for training gigantic models, having to pay for the service and rather steal it from your competitors.

-

Other risks: Other minor attacks include membership inference attacks and poisoning attacks, where the adversary tricks the model into revealing whether a certain datapoint was used to train a model or not and if the adversary can inject malicious data to your training pool to get the model to learn something it was intended to learn respectively.

Defenses Against Evasion

Technique 1: Adversarial Training

Adversarial training uses the Fast Gradient Sign Method 2 within the objective function to regularize the model effectively. The objective function, defined in the equation, can be viewed as considering the worst case error (when the attacker perturbs the data) and minimizing it by adding to it. As reported by Goodfellow et al., the error rate on adversarial samples reduced from 89.4% down to 17.9% on the MNIST dataset after Adversarial Training which demonstrates the robustness achieved by the defense.

\[\bar J(\theta, x, y) = \alpha J(\theta, x, y) + (1 - \alpha)J(\theta, x + \epsilon \text{sign} (\nabla_xJ(\theta, x, y)) \label{at}\]Technique 2: Minimizing Adversarial Risk

To train classifiers that are robust to evasion attacks, we need to estimate the performance of the classifier when it is exposed to adversaries. We first differentiate between traditional risk and adversarial risk. The traditional risk and adversarial risk of a classifier are defined below.

\[R(h_\theta) = \mathbf{E}_{(x,y)\sim\mathcal{D}}[\ell(h_\theta(x)),y)] \label{trad_risk}\] \[R_{\mathrm{adv}}(h_\theta) = \mathbf{E}_{(x,y)\sim\mathcal{D}}\left[\max_{\delta \in \Delta(x)} \ell(h_\theta(x + \delta)),y) \right ] \label{adv_risk}\]where \(\mathcal{D}\) denotes the true distribution and \(\Delta(x)\) denotes the allowable perturbation region on the sample. Classifiers robust to adversarial attacks are trained by minimizing adversarial risk forming a min-max objective as stated in Madry et al. 3. With this objective in mind, the optimization can be split into:

-

Inner Maximization: This can be solved by first attacking the model to generate adversarial samples which are done by computing the gradient with respect to the perturbation \(\delta\) itself and performing gradient descent to maximize the objective. The Fast Gradient Sign Method 2 adjusts the perturbation in the direction of the gradient \(g\). The sign of this gradient is used to generate the adversarial sample. Projected Gradient Descent 3 works similarly, except that it does not use the sign and projects the perturbations onto a ball of interest (usually \(l_\infty\) or \(l_2\)).

-

Outer Minimization: This step is crucial to obtaining robust classifiers. Here we minimize the adversarial loss, which represents the worst-case loss that the network can encounter if it is exposed by adversaries (equivalently the inner minimization). The minimization can be achieved using standard optimizers such as SGD and Adam.

The key aspect of adversarial training is to incorporate a strong attack into the inner maximization procedure.

Technique 3: Defensive Distillation

Defensive distillation 4 increases the robustness of deep neural networks by altering their last layer. The last layer is the temperature softmax (inputs to the softmax are divided by factor $T$ temperature). Defensive distillation can be stated as a three-step procedure:

-

A neural network \(f\) is trained, with the temperature of the final layer softmax being greater than 1.

-

This neural network is used to infer predictions on the dataset, forming a new dataset. We now have class probability vectors instead of hard classes associated with each training data point

-

A new instance of \(f\) is trained using the dataset prepared in step 2 at the same temperature as the first neural network.

Training a network with this explicit relative information about classes prevents models from fitting too tightly to the data, and contributes to a better generalization around training points.

Defenses Against Extraction

Technique 1: Deceptive Perturbation and Prediction Poisoning

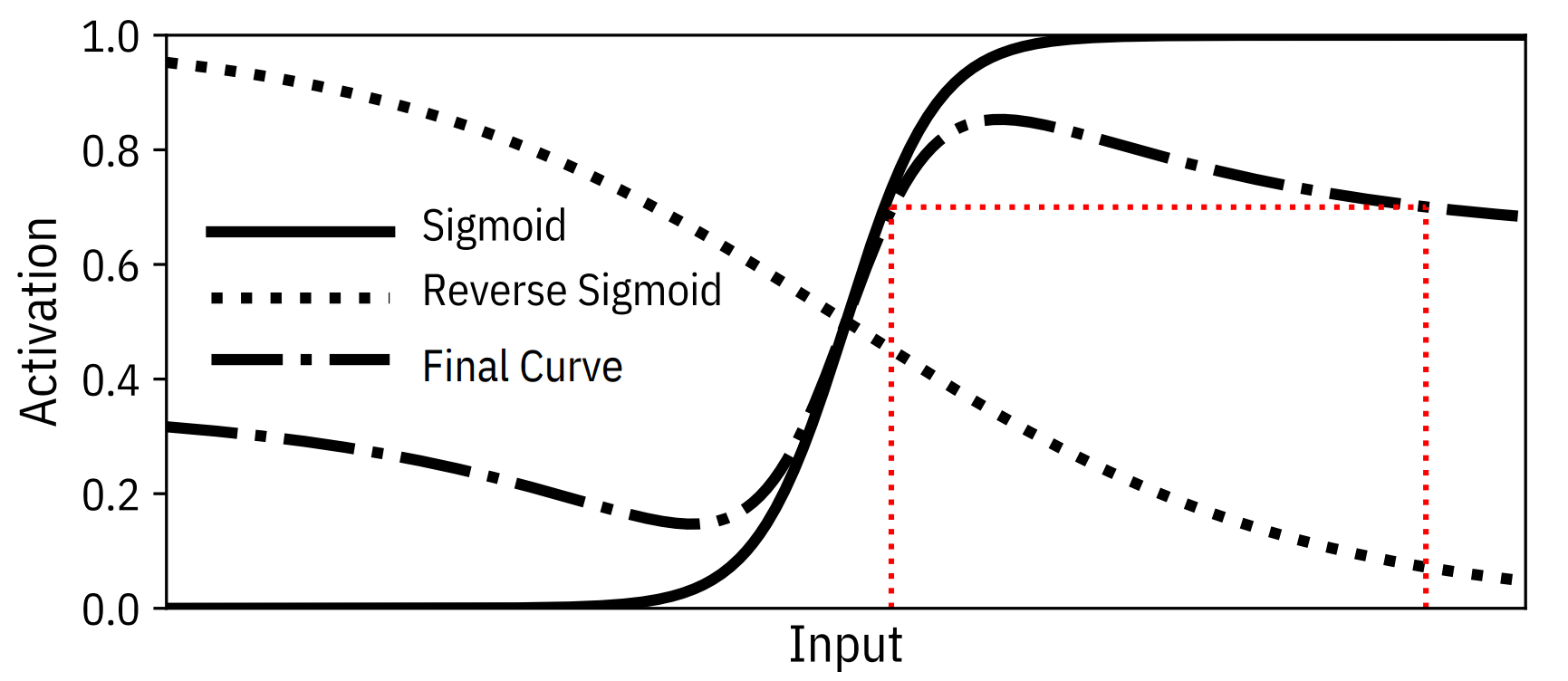

Deceptive Perturbation technique 5 perturbs the softmax activation function which generates confidence scores. They add smart noise to the output probability vector which maintains the output class label and does not harm the accuracy. The noise added is such that in an attack attempt, it maximizes the loss of the extracted model thus slowing down the model stealing attack. With the above constraints, they obtain the Reverse Sigmoid perturbation. This perturbation, when added to an existing neural network with a Sigmoid layer results in the final activation being non-invertible, hence making the inversion (extraction) attack very difficult. The Sigmoid, Reverse Sigmoid and its combination have been depicted in the figure below

Orekondy et al. 6 propose using prediction poisoning to throw the attacker off the mark. They perturb the prediction in a controlled setting such that it still remains useful for the benign model user while making it difficult for an adversary to use it for model extraction. A common denominator of many attacks is estimating and using the first-order approximation of the empirical loss. To counter this, we perturb the prediction vector such that the resulting gradient signal maximally deviates from the original gradient while keeping the perturbation inside allowable perturbation reigon and keeping it meaningful for benign user. it meaningful for casual users. They show that this problem reduces to a non-standard, non-convex constrained maximization objective.

Technique 2: Detecting and Rejecting Adversarial Queries

Model extraction attacks with no access to the training data generate synthetic data to train the clone model. This can be generated using Generative Adversarial Networks or using Jacobian Based Data Augmentation Techniques. These queries are termed as adversarial queries.

Juuti et al. 7 proposed that adversarial queries with the target of exploring decision boundaries will have an unnatural distribution. We expect an innocent model user’s queries to be distributed in a normal way but to probe the input space as effectively as possible and collect as much information as possible, the adversary artificially controls the distance between subsequent synthetic searches. Adversaries are also expected to use a combined query distribution of natural and synthetic samples all coming from different distributions. Common attack techniques have their query distribution which deviates a lot from the normal distribution. PRADA (Protecting Against DNN Model Stealing Attacks) tries and detects a deviation of search queries from a normal distribution and based on that rejects adversarial attacks.

The detection criterion starts with calculating the minimum distance between a new queried sample and all the previous samples that have been queried. These minimum distances are stored in a set. The detection is based on how closely the distances in the set fit the normal distribution. Several metrics such as the Shapiro-Wilk test statistic exist to perform this normality test. If the test statistic is below a threshold, an attack is considered to occur.

Another detection strategy known as Forgotten Siblings, proposed by Quiring et al. 8, can defend models with linearly separable classes. It uses the closeness to the decision boundary as a metric to detect an extraction attack against a decision tree. As discussed in the preceding paragraph, adversaries generate synthetic data closer to the boundary to learn the boundary closely. This feature is exploited by the defense and a margin is set along the boundary. If a high ratio of queries lies within the security margin defined, an attack is detected and can be avoided.

Technique 3: Model extraction warnings

Another class of defense strategies expects the model owner to record and analyze the query and response streams of both individual and colluding model users. If this monitor detects any malicious behavior, it will warn/reject the query inflow. Kesarwani et al. 9 present such an approach. The crux is to limit the amount of information learned by any user to a safe level. The monitor computes the information gain of the users based on their queries received thus far. In order to do this, it uses a validation set, \(\mathrm{S}\), supplied by the model owner that has a distribution similar to the training set. Generalizing on this metric, we define a metric called the information gain of a decision tree \(\mathrm{T}\) with respect to a given validation set \(\mathrm{S}\). This is an accurate descriptor of the reduction in entropy of a training set when the user makes a prediction according to the information he currently has.

\[I G_{\text {tree }}(S, T)=\operatorname{Entropy}(S)-\sum_{l \in l e a f(T)} \frac{\left|S_l\right|}{|S|} \operatorname{Entropy}\left(S_l\right)\]Similarly, one can apply the equation to compute the information gain of the model owners source decision tree \(T_O\) as \(I G_{\text {tree }}\left(S, T_O\right)\). It was observed that information gain accurately captures the learning rate of the user’s model.

A model owner is also concerned about if any \(k\) of the \(n\) users accessing the deployed model are colluding to extract it. The approach used for a single user can be extended to prevent against this too. We can greedily keep a tab on the k users with the highest information gain and using their combined query data, build an information gain tree. If this shoots above the acceptable limit, we start greedily refusing queries from the most learned users.

Technique 4: Label Smoothing and Logit squeezing

Label smoothing 10 converts one-hot label vectors to warm label vectors. We apply this trick to represent a low-confidence classification, which forces the classifier to produce small logit gaps. Label smoothing is a general regularisation trick used in the training of ML models.

\[\boldsymbol{y}_{w a r m}=\boldsymbol{y}_{h o t}-\alpha \times\left(\boldsymbol{y}_{h o t}-\frac{1}{N_c}\right)\]Logit Squeezing 10 is another way of forcing the model to produce low-confidence logits. We add a regularization term to the training objective that penalizes large logits.

\[\underset{\boldsymbol{\theta}}{\operatorname{minimize}} \sum_k L\left(\boldsymbol{\theta}, X_k, Y_k\right)+\beta\left\|\boldsymbol{z}\left(X_k\right)\right\|_F\]Lee et al. 11 showed that aggressive logit squeezing with squeezing parameters \(\beta = 10\) and \(\alpha = 20\) leads to the training of a more robust model than is competitive with adversarially trained models when attacked with PGD-20. Interestingly, it also achieves higher test accuracy on clean examples.

-

https://thenextweb.com/news/some-teslas-have-been-tricked-into-speeding-by-tape-stuck-on-road-signs ↩

-

I. J. Goodfellow, J. Shlens, C. Szegedy, ‘Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples’. arXiv, 2014. ↩ ↩2

-

A. Madry, A. Makelov, L. Schmidt, D. Tsipras, A. Vladu, ‘Towards Deep Learning Models Resistant to Adversarial Attacks’. arXiv, 2017. ↩ ↩2

-

N. Papernot, P. McDaniel, X. Wu, S. Jha, A. Swami, ‘Distillation as a Defense to Adversarial Perturbations against Deep Neural Networks’. arXiv, 2015 ↩

-

T. Lee, B. Edwards, I. Molloy, D. Su, ‘Defending Against Machine Learning Model Stealing Attacks Using Deceptive Perturbations’. arXiv, 2018. ↩

-

T. Orekondy, B. Schiele, M. Fritz, ‘Prediction Poisoning: Towards Defenses Against DNN Model Stealing Attacks’, ICLR, 2020 ↩

-

M. Juuti, S. Szyller, A. Dmitrenko, S. Marchal, N. Asokan, ‘PRADA: Protecting against DNN Model Stealing Attacks’, CoRR, abs/1805.02628, 2018 ↩

-

E. Quiring, D. Arp, and K. Rieck, “Forgotten siblings: Unifying attacks on machine learning and digital watermarking,” in 2018 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS\&P), 2018, pp. 488–502 ↩

-

M. Kesarwani, B. Mukhoty, V. Arya, S. Mehta, ‘Model Extraction Warning in MLaaS Paradigm’. arXiv, 2017 ↩

-

A. Shafahi, A. Ghiasi, F. Huang, T. Goldstein, ‘Label Smoothing and Logit Squeezing: A Replacement for Adversarial Training?’ arXiv, 2019. ↩ ↩2

-

T. Lee B. Edwards, I. M. Molloy, D. Su, ‘Defending Against Neural Network Model Stealing Attacks Using Deceptive Perturbations’. IEEE Security and Privacy, 2019. ↩